Teach Us All:

Classroom Tour:

While the "Introduction to Culturally Relevant Pedagogy" video was short, I found that it had numerous connections to previous pieces of media we have discussed in class, especially Lisa Delpit's article. In the video, a discussion was held on the cultural filters through which we perceive the world, and how these filters are applied in schools. Students analyze what an instructor says through their own cultural lens, not necessarily the instructor's. We expect kids to inherently know the school's culture, though, and so look down on or punish them when they do not adhere to it. However, there is no way for them to automatically know a given culture. These ideas align closely with what Delpit has to say about the Culture of Power and the Silenced Dialogue. Instructors and students each applying their cultural filter to an interaction and arriving at separate conclusions is a prime example of the "communication dissonance" that Delpit discusses. Furthermore, the assumption that students will inherently fit into the school's culture exemplifies the Culture of Power, as it is assumed that the school's authorial culture is superior. The idea that teachers, instead of forcing this adaptation, serve as "cultural translators," aligns with Delpit's claim that acquiring power is easier when the culture's rules are explicitly stated. After all, it is easier for students to behave if they know what is expected of them.

The discussion about the challenge of separating a student's culture from their entire identity also seemed to serve as a companion to Precious Knowledge, albeit counterintuitively. As the video states, a student's connection to their culture can vary depending on their circumstances and does not provide a complete picture of who they are. I found that the classes in the film reflected that. While they certainly did primarily focus on culture, they were also about the individual students. Some of the students in the film said that the classes helped them discover who they are, and some of the lessons shown focused on personal development. When a teacher serves as a "cultural translator" for their students, they support their individual students by learning their individual stories.

While not something we watched in this class, the video reminded me of a film I saw at CCRI called Starting Small (I could only find a trailer, not the full version). The film followed classes with an anti-racist curriculum, which really focused on exposing kids to people different than themselves. One class brainstormed ways to make their building more accessible for a guest speaker in a wheelchair, and another class had the opportunity to meet a local Native American leader and ask him about his culture. Although the focus of those curricula was a bit different than what was discussed in this video, they had the basic idea of cultural exchange in common.

I agree with most of the points in Kohn's chart. However, I found myself a bit hesitant about his classification of sticker charts as a negative, as it indicates that students are ranked. I follow his basic idea, since it unfairly humiliates students, but I have seen charts like these for classes as a whole that work well. For example, in a program I volunteer in, we give classes charts for anonymously recording both altruistic and "mean" behavior. While we do get some tattletales regarding the poor behavior chart, the altruistic behavior chart seems to work wonders in encouraging more of that behavior. So, my question is, are charts always negative, and I am just defensive about my program, or can they be used effectively?

I can best describe reading this article as gaining a new vocabulary. Many of Delpit's points are ideas I have seen alluded to before, or concerns I have had myself, but I have never seen them put together and discussed in such an effective way. As excited as I am to teach, one of my main concerns has been how to effectively interact with students who do not share my own background. I am very much, at least demographically, one of the White, middle-class, liberal/progressive teachers who tend to ignore input from those in minority groups. I do not want to be one of those teachers. I want to respect my student and colleague's ideas, regardless of how they align with my own. It's common knowledge that there are multiple learning styles, so why can't there be multiple effective teaching styles as well? As interesting as learning the theory behind education and development is, it cannot completely dictate what happens in the classroom. Some of the best educators I have seen are people who do not know about Vygotsky or Piaget, but know how to connect with students.

I also think that discussing matters of cultural power in the classroom is simply responsible teaching. One of the main purposes of public education is to make students responsible citizens, so giving them the necessary tools to function in society should be a given. It may be unpleasant to discuss, but who does and does not implicitly have power is part of it. As Delpit references, acknowledging that power can make those who have it uncomfortable, leading to pushback. Alternatively, some do not recognize it and internalize a deficit model. In my volunteering experience, for example, I have regularly seen parents who cannot volunteer deemed as uncaring or lazy for not taking more of a role in their child's education (always said by White, middle-class parents). Those working-class parents receive a lot of flak just because their parenting differs from the White, middle-class standard. Working-class parents, though, don't have the same resources as middle-class parents, meaning that they have to raise their children differently to function in a different role.

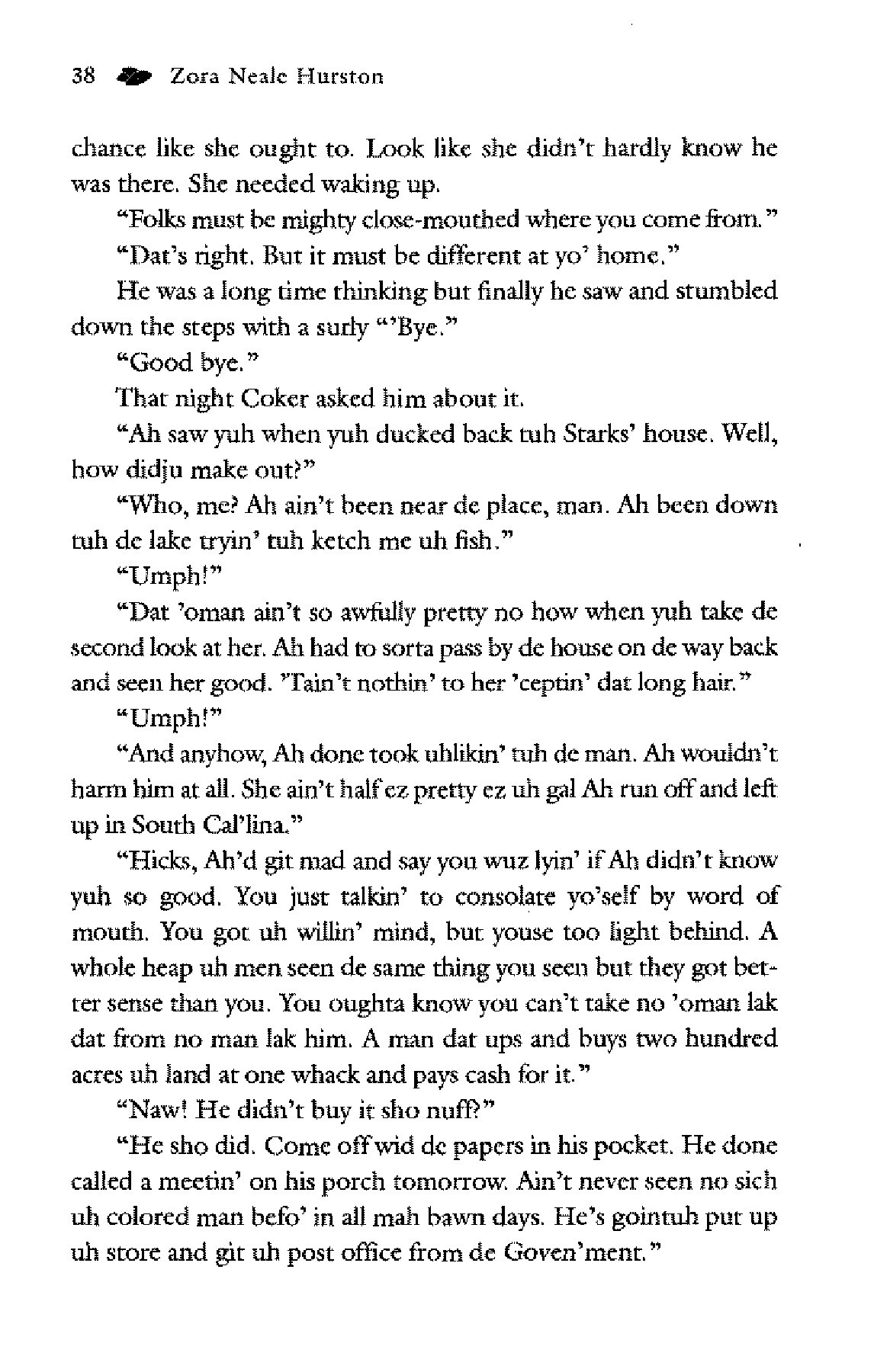

On the flip side, I have seen students dismiss writing not done in standard English as a waste of time. One of my favorite assigned books in high school was Their Eyes Were Watching God, which heavily features written dialects. My class of White, middle-class students all dismissed the book as uninteresting or too difficult because it did not fit into the structure we were used to. The book addresses heavy themes, much heavier than what is regularly discussed in K-12 schools, all from the perspective of a Black woman. It was a unique educational experience, and one I treasure for expanding my horizons. Experiences like that shouldn't be viewed as threatening or wrong because they do not fit the status quo.

|

| This page from Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston demonstrates the heavy dialect in the novel's dialogue. |

From what I can tell, some of the issues with disregarding the voices of minority teachers is implicit bias, or biases that someone may not even be aware they have. Delpit references that some approaches can, intentionally or not, ignore the intelligence and critical thinking skills of those in minorities. How can we recognize and check our own biases in the classroom to make sure we respect the ideas of our students and colleagues?

As strange as it may sound, I found this article incredibly validating, especially concerning social studies/history education. As a White student, my experiences closely line with what the research describes, at least for elementary school and the beginning of middle school. We learned about American history from a Euro-American perspective, up to excluding the role of slavery in the Civil War and learning that the Civil Rights movement ended racism. In middle school, though, I read a book called All American Boys, which completely changed my perspective. The book is about police brutality and the Black Lives Matter movement, neither of which I had heard of. Suddenly, I saw that the world was a much less idealistic place than I had thought, and that racism was unfortunately alive and well. Then, when I was in high school, I got to see a renewed sense of urgency with the murder of George Floyd.

|

| All American Boys, by Jason Reynolds (one of my favorite authors) and Brendan Kiely |

Along with these revelations, I began to notice biases in the curricula, especially in history. Pretty much every trend Sleeter references about the depictions of minority groups holds true in my experience. Like some of the students she interviewed, I began to tire of learning about the accomplishments of the same White people in the same stories, especially when my growing love for history revealed that there were many other important stories to tell. To see research validating these trends and concerns is, as I said, validating, since it shows me it does not just come from one White girl.

That said, the article validated some of my fears as well. I am terrified of accidentally becoming a teacher who only teaches the Euro-American perspective. After all, that is the baseline I grew up with, and that many of my students will grow up with as well. Most curricula still focus on that perspective. And, as Sleeter addressed, parents tend to find any mention of race divisive. I have had a parent request that her child be withdrawn from a program I help present because, while discussing inclusion, another child said that discriminating based on race is inappropriate. To her, we were promoting division. So, the temptation to stay in the "mainstream" perspective is strong, and it sounds like a temptation many teachers, particularly White teachers, fall to. In doing that, though, I would be doing a disservice to my students, as I would be denying them meaningful information. I know it is still too soon to worry so much about my own pedagogy, but these concerns are still worth considering.

How do we meaningfully incorporate multiple ethnicities into our teaching? As a future history teacher, I already have a good idea of how to do this - by simply acknowledging multiple historical perspectives in my classes. Aside from the importance of respecting diversity, to ignore underrepresented perspectives is simply bad history. In other disciplines, though, how would you go about incorporating diversity in the curriculum?

While reading about the deficit model found in many education systems, I found myself thinking of how I had seen this during my own education. In elementary school, for example, I remember a few instances where I witnessed teachers overly focusing on the poor behavior of classmates. Once, I even had a teacher ask me to report to her any time one of my friends misbehaved. This was the first time I can recall starting to question why the system worked the way it did, because while my friend was a bit hyperactive, she was intelligent and one of the nicest kids in our class. I told my parents about this, and they reported the teacher's actions to the principal, who reprimanded the teacher. However, teachers regularly questioned my friend. Unsurprisingly, with the lack of support she received from most of the adults in our school, she started to fall behind once we reached middle school. She's thriving now, but her case was one of the first I saw in which the schools failed a student.

Something similar happened to my best friend's brother. From the time we were young, he was rude and acted out. Teachers responded to his behavior as you would expect. My friend's parents did not take kindly to the focus on his poor behavior, to the point that they pulled him and my friend out of most school activities out of spite. Again, once we reached middle school, I noticed this lack of involvement started to affect them. While my friend was able to find her own support system, her brother never did. Today, he's drifting through, another soul failed.

On a more positive note, I have also seen how building assets, especially external assets, can help students. In Warwick, I volunteer in most of the elementary schools where I help teach an anti-bullying program. We visit each class once a week for ten weeks, and every time I get to watch the students bloom. As we teach them prosocial behaviors and emotional coping skills, I get to watch them mature. At the risk of bragging, it is clear that part of it is forming connections with adults from the community. Especially in my case, the students are fascinated by a working college student who takes time to hang out with them. I find the experience just as rewarding as the students, if not more so.

|

| This is the "Peaceable Being," the first lesson in our anti-bullying programs. The words inside the silhouette are positive behaviors, and the words outside are negative behaviors. |

I fully agree with the argument the text makes for asset-based schools. How, though, do we change the system at large to reflect that? The authors do mention strategies that individual teachers can use to support students. That, though, doesn't address cultural change. What can we do as educators to promote school-wide or district-wide change?

Many of the overarching themes Anyon discusses are concepts I have heard before. In several of my previous classes, we have discussed how socioeconomic status affects a child's development and education. The trends discussed, most of which come to kids from a lower SES being at a disadvantage, were not new to me. However, as I read and thought about how I have experienced these trends, I began to wonder about how these correlations have played out in Rhode Island.

On the RIDE website, there is a link to the Assessment Data Portal, through which the public can look at the results from exams administered in schools. For the sake of quick research, I looked at RICAS ELA/Literacy scores. I began by comparing scores from schools in my district, Warwick. The scores of our most affluent school (Cedar Hill) far surpassed our least affluent (Oakland Beach). There is a 24.5 percentage point difference between the passing percentages at each school. Having been in both schools, I have noticed a marked difference in the resources available. Cedar Hill is technology-heavy, provides numerous supports to students and teachers, and has heavy parent involvement. Oakland Beach, on the other hand, had an HVAC system so old that the school had to be moved to the administrative building for a school year to allow for repairs. To me, the empirical data from the testing seemed to confirm my anecdotal experiences.

From there, I wanted to compare districts. I chose the town with the highest median family income, East Greenwich ($198,007), and the lowest median family income, Central Falls ($50,275). Looking at the same test, there was a 51.2 percentage point difference in passing scores. Clearly, SES impacts education. Again, my own experiences confirm this. While I have not heard too much about East Greenwich schools, Central Falls schools are always used as the go-to negative example. I have had teachers who said teaching there was like Hell (though I do not necessarily believe them). The town has one of the highest poverty rates in the state, including about 28% of the under-eighteen population. East Greenwich, by comparison, only has about 4% of its children in poverty.

Khan argues that our current education system stems from precedents set by generations before us, which should now be reevaluated to be more effective for the modern world. The basis of the current system is the Prussian Model, itself based on the philosopher Johann Fichte. Fichte argued for a system that would shape individuals into ideally obedient workers without an outlet for their own development. So the Prussian model was born, which divided both the day and ideas, meaning that students would not have the opportunity to piece various ideas together or discuss them with their peers. Despite the stifling nature of the system, it marked an important innovation in education, as it was one of the first systems to implement universal basic education. In the nineteenth century, Horace Mann introduced the system to the United States, where it was eventually implemented in every state. In 1892, the Committee of Ten from the NEA designed the basis for the current set of subjects and grades in American Schools. We have been working on their model for the past century.

|

| Johann Gottlieb Fichte |

While these systems may have been innovative for their time, they do not necessarily meet the needs of modern students well. Testing, for example, does not always measure student mastery. Depending on how well the test was designed, it can at best capture a snapshot of a student, and at worst, measure nothing. Take the example Khan provides of state testing in New York. Scores fluctuated as different groups designed the state's standardized testing. Certainly, the student populace did not drastically change in ability, but the quality of the testing did. Furthermore, testing often focuses only on analytical thinking, leaving practical and creative students by the wayside, which can often lead to them being tracked into lower-level classes. All of this taken together, it seems clear that the current practices in place need to be reevaluated.

Similarly, the video "A Short History of Public Schooling" also discusses the Prussian model and its influence on American schools, with a greater emphasis on its spread in the United States. Horace Mann, the first Secretary of Education in Massachusetts, imported the Prussian model into American schooling in 1837. He saw it as the "great equalizer," allowing every child to become the ideal factory worker in an increasingly industrial world. In 1852, a compulsory attendance law was passed, requiring all children to attend school. These practices spread throughout the US, with 34 states having similar policies. By 1918, all states required compulsory elementary education. While universal basic education is somewhat of an equalizer, as Mann intended, the system stifles students' imagination, forcing them to fit into set roles in a post-industrial world.

These pieces make convincing arguments for the eventual restructuring of our educational system. However, neither seems to offer an alternative, at least in the format we were given. Khan's piece is part of a larger book, so I assume he shares his ideas there. Similarly, the documentary the video clip is from seems to advocate for homeschooling. However, since we are all here to become teachers, those solutions are not particularly helpful for us. What changes to the system would be beneficial for current students? Further, how do we implement these changes? As Khan said, it would require a fundamental shift in our society, which, while not impossible, is difficult. So, how do we do it?